Paul says of Jesus that “He is the image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1). “Image” is “icon”. Jesus is the icon of the invisible God. God, who cannot be seen, is seen in Jesus. In Jesus we see the one who cannot be seen. Jesus is emphatically the icon of the invisible God. Wherever God is seen, it is Jesus. We come to the Father through the Son. We come to the invisible one through the Nazarene. His is the one name given under heaven by which men can be saved. He is the centre of history, the singular portrait that God has painted of himself in the mud of this planet. But how can we see Jesus?

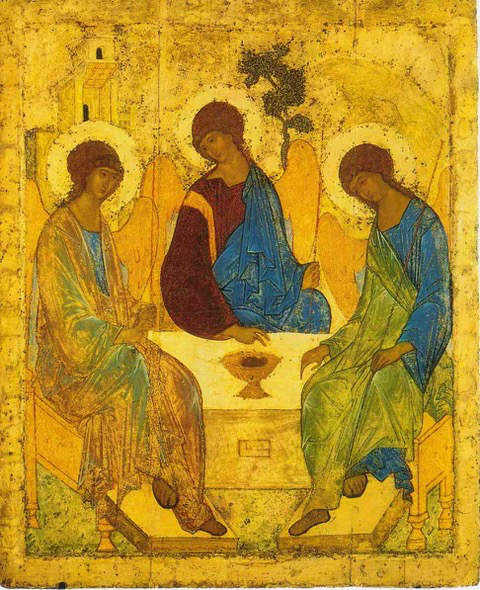

When I started university, heady with the feeling of leaving my hometown and starting life my own, heady with the feeling of wanting to achieve my potential, to become who I could, I bought two aspirational posters for my college dorm wall. One was Raphael’s school of Athens, and the other was Andrei Rublev’s The Trinity. Knowing nothing of the history of Christian art or iconography, but searching through it a little, this image spoke to me so clearly. And I want to try to convey what it has said to me and has come to say to me now in a couple paragraphs.

Rublev’s The Trinity is the icon of the invisible God. Its role in Christian imagistic imagination is absolutely and irrevocably foundational. It sits on the base of the brain of the Christian hive mind, and even before that was conceived in the womb of God as the portrait that they wanted to paint of themselves, not in mud, but in paint, even in gold. It was arguably the first piece of mainstream church iconography ever in the world to dare to directly represent the Trinity. The three in one, the directly contradictory mystery of who God is, the statement of their not being knowable or representable, Rublev represented.

He did this by means of painting the visit of three angels to Abraham by the trees of Mamre. In the background are depicted the trees, Abraham’s house, and the cliff from which two of the angels go on to survey and judge Sodom and Gommorah. In Genesis, these three are various named “men”, “angels”, and “the Lord”. The utter mystery of what God is, or how God could appear angelically, let alone in flesh, is conveyed in this confusion of account, directly verbal, directly remembered from Abraham’s baffled mind. God the baffler is shown in these angels, and early Christian theology saw in this theophany one of the earliest indications of God’s trinary being – an icon of the trinity to Abraham.

So Rublev’s painting is something like the earliest widely memorable image of the earliest widely memorable appearance of the trinity on earth. I see in it the solidity of the icon itself, the shimmering gold of the appearance of the invisible God. The one who has appeared and shown who He is by saying “I am invisible and cannot be represented”. The Jesus who has hidden himself at his Father’s right hand now here again on paper, well, on a church wall, well on my parent’s kitchen wall, well on computer screens, well in our minds whenever we want to imagine it. I get the sense when looking at this icon of peering right into the baffling mystery of the singular revelation of God in Christ by His Spirit, I feel I see the unity of Incarnation and Trinity, I feel a peace in my mind’s lack of understanding, and a recognition of my seeing and knowing it nevertheless. I feel that the truth of the potential I wanted to realize in myself those years ago shines back at me in my failing to grasp it. In this icon I see The Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, also that of God, angel, human being, of unknowable, knowable, known, of idol, icon, art, of what is not, what is potential, and what is.

Leave a comment